Delicious, deadly, magical, intoxicating, mysterious. Throughout history mushrooms have gained many varying reputations, considered both food and foe. Today it is easy for us to find safe, tasty mushrooms at the grocery store, but it wasn’t always this way. Over the years reckless mushroom hunters have thrown caution to the wind with sometimes fatal results, giving food-safe mushrooms a bad reputation. It’s resulted in two very different categories of people—mycophiles (those who love mushrooms) and mycophobes (those who fear mushrooms). Then there are folks like me, who fall somewhere between adoration and trepidation. I enjoy mushrooms, but I’ve heard enough horror stories about them to be cautious; you won’t see me hunting for wild mushrooms without an expert guide by my side. As we’ve familiarized ourselves with their many different species, mushrooms have become less forbidding. With the recent focus on locally sourced food and foraging, the allure of the mushroom doesn’t seem to be slowing down. If anything, mushrooms are now more popular than ever.

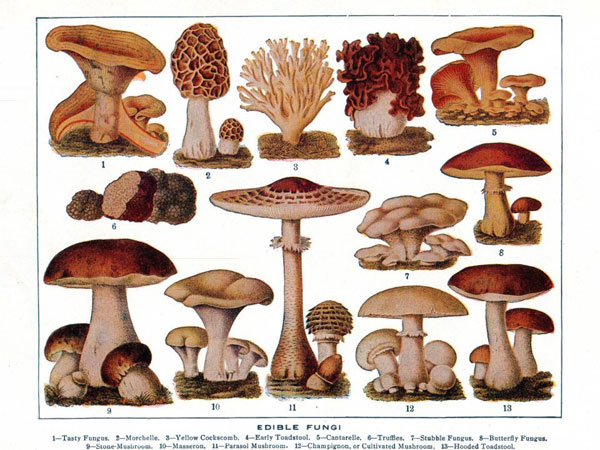

Mushrooms are often lumped into the vegetable category, though most of us know that they are actually a fungus. Today the most commonly consumed variety is the button mushroom, or Agaricus bisporus, which makes up about 40 percent of the mushrooms grown around the world. The name “mushroom” has been given to over 38,000 varieties of fungus that possess the same threadlike roots and cap. These threads, sometimes referred to as “gills,” are responsible for giving mushrooms like portobellos their meaty taste and texture. As air passes through the threads moisture evaporates, giving the mushroom a rich heartiness you can really sink your teeth into.

A great deal of the mystery surrounding mushrooms stems from their association with poisonings and accidental deaths. The famous French philosopher Voltaire was once quoted as saying, “A dish of mushrooms changed the destiny of Europe.” He was referring to the War of Austrian Succession that followed the death of Holy Roman Emperor King Charles VI. The king’s untimely demise may have been a result of eating amanita, or “death cap,” mushrooms. On the other hand, mushrooms have also been praised for their medicinal properties thanks to their heavy dose of protein, potassium and polysaccharides, which contribute to healthy immune function.

Of course, you can’t have a conversation about mushrooms without touching on the intoxicating variety. Though we may associate hallucinogenic mushrooms with the culture of the 1960s, archaeological evidence suggests that these types of mushrooms served religious and spiritual purposes centuries earlier. Siberian shamans and Vikings are believed to have consumed hallucinogenic fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) mushrooms during religious ceremonies. According to the Mixtec Vienna Codex (13-15 centuries AD), mind-altering mushrooms were used in religious ceremonies in ancient Mexico. Roman Catholic priests also observed and recorded the consumption of hallucinogenic mushrooms by native peoples after the conquest of Mexico in 1519. After the effects of the mushrooms had worn off, the natives would discuss their visions of the future. We now know that these effects were not caused by magic, but rather by the psilocybin and psilocin found in some mushrooms.

For centuries relatively little was known about mushrooms, and for a long time the Eastern half of the world was considered mostly mycophilic, and the West mycophobic. This all changed when the French introduced mushrooms into their haute cuisine. It wasn’t long before the rest of the world began to embrace the mushroom. By the late 19th century, Americans were cooking up mushrooms in their own kitchens. Prior to this time, mushrooms were mainly reserved for use in condiments. Inspired by the French, Americans took mushrooms to a whole new level of devotion. Clubs dedicated to foraging, identifying and cooking various varieties of fungi began popping up all over the country. Even today, locally foraged mushrooms are worth their weight in gold... just ask any mushroom hunter in search of morels after a spring rain shower.

If there is a crown jewel in the realm of fungi, it is the truffle. Referred to as the “diamond of the kitchen” by famous French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, truffles are one of the most expensive foods in the world. They grow near tree roots, most often oak, hazel, beech and chestnut, about 3-12 inches below ground. They are sniffed out by dogs and pigs that have been trained to recognize the truffle’s distinct odor. once a truffle has been located, the trufficulteur (truffle farmer) will very carefully clean the surrounding area to check for ripeness. It is important to never touch the truffle with your bare hands, as this can cause the precious fungi to rot. If the truffle is not yet ripe for the picking, it is recovered and left to reach maturity. This long and labor-intensive process is the reason behind the hefty price tag.

As America’s interest in mushrooms grew, entire cookbooks were devoted to them. One of the first English language mushroom cookbooks is Kate Sargeant’s One Hundred Mushroom Receipts (1899). Sargeant’s work includes some fabulous Harry Potter-sounding recipe titles including “Coprinus Comatus Soup (Shaggy Mane),” “Lepiota Procera Stew,” and “Baked Tricholoma Personatum.” In the book’s introduction, Sargeant describes the changing American attitude towards mushrooms at the turn of the century:

The general opinion in this country regarding mushrooms has been, that with one or two exceptions, all forms of fungus growth are either poisonous or unwholesome, but it is very gratifying to observe the change that is rapidly taking place in the public mind. Soon public opinion will acknowledge that it is an established fact that the great majority of the larger funguses, especially of those that grow in fields and other open places, is [sic] not only wholesome but highly nutritious.

- Kate Sargeant, One Hundred Mushroom Receipts (1899)

Sargeant also acknowledges the mushroom’s status as the “meatiest” of vegetables, noting that the butcher bill would surely decrease if we would replace some of our meat entrees with mushroom preparations. It seems Sargeant was ahead of her time; today many vegetarians replace the beef in their hamburgers with a seasoned, roasted portobello cap.

Some of the earliest American mushroom recipe preparations were for mushrooms baked on toast in cream sauce. In Studies of American Fungi (1911), Sarah Tyson Rorer suggests baking the mushroom under a glass bell. The bell was then lifted at the dinner table so that “the eater may get the full aroma and flavor from the mushrooms.” If you’d like to make a similar vintage mushroom recipe, with or without the glass bell, try this one from Cooking Club Magazine, published in February 1908. It was printed not long after Americans jumped on the mushroom bandwagon!